Freedom's Fatal Flaw: Why Frisian Liberty Collapsed While English Authority Endured

Though separated by the North Sea, early medieval Frisia and Anglo-Saxon England shared deep Germanic roots in their legal and social systems. Both relied on customary law, wergild payments, and communal assemblies inherited from their common ancestral traditions. Yet from these shared foundations, each society developed markedly different approaches to governance, law, and authority - creating ripple effects that would echo through centuries of different civilizations, influencing later political developments in ways both direct and unexpected.

Where Anglo-Saxon England experienced centralization and royal authority, Frisia maintained extensive decentralization and local autonomy. English kings like Æthelberht and Alfred synthesized Germanic customs with Christian kingship and Roman administration, creating sophisticated legal codes and unified court systems. Meanwhile, Frisian communities preserved their ancient assembly traditions on terpen and at the Upstalsboom, maintaining forms of confederated governance that resisted external authority for centuries. These contrasting responses to similar pressures would prove to have vastly different long-term consequences - revealing how the very strengths that made each system successful could, under changing circumstances, become sources of vulnerability.

Origins: Lex Frisionum and Anglo-Saxon Dooms

Anglo-Saxon Law Codes (Dooms)

Anglo-Saxon written law began earlier, around 602 CE when King Æthelberht of Kent issued the first Germanic-language law code. Unlike continental "barbarian" codes written in Latin, the English recorded laws in Old English - an unprecedented decision that preserved their legal vocabulary.

Æthelberht's Laws established sophisticated legal procedures including detailed compensation schedules, protection for the Church, and complex regulations for marriage and property. This earliest written Germanic law code (predating Frisian codification by nearly 200 years) demonstrated English kings' early embrace of legal administration and systematic governance.

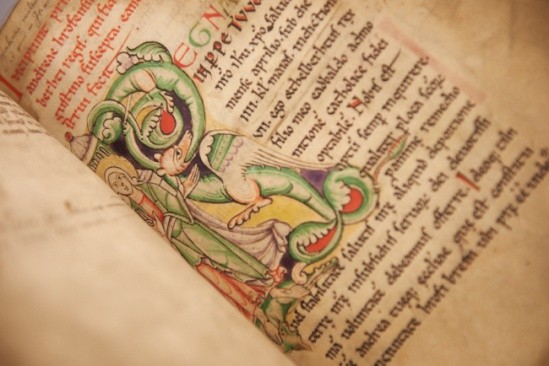

These laws survive in the 12th-century Textus Roffensis manuscript, now recognized by UNESCO as documentary heritage of national significance. The codes established a pattern of royal legislation that would evolve into England's unified legal system.

Frisian Freedom and the Lex Frisionum

The concept of "Frisian Freedom" emerged after Charlemagne's conquest of pagan Frisia by 785 AD. While later medieval documents claimed Charlemagne granted Frisians a charter freeing them from feudal servitude, historians now know these charters were fabricated between 1297-1319 to justify their unique autonomy. This historical puzzle reveals much: why did 14th-century Frisians feel compelled to invent an imperial origin for their freedom? The fabrication suggests their decentralized system had become so unusual by the Late Middle Ages that it required legendary justification.

The authentic Lex Frisionum, recorded in Latin during Charlemagne's reign, codified Frisian legal customs including compensation schedules, social classes, and legal procedures. Uniquely among Germanic codes, it prescribed equal fines for killing women and men of the same rank.

Unlike centralized Anglo-Saxon legislation, the Lex Frisionum reflected a more decentralized approach. While it provided standardized compensation values and legal procedures, enforcement remained largely local. The code preserved ancient Germanic traditions of assembly justice while acknowledging Carolingian overlordship, creating a unique hybrid that would influence centuries of Frisian legal identity.

While both systems began as extensions of older Germanic customs, Frisia's collapse of Carolingian central power left a vacuum filled by self-governing farmer republics. By 1100, feudal counts had vanished from coastal Frisia, creating unique conditions for local governance under loose Imperial oversight.

Wergild and Social Hierarchies in Justice

Both Frisians and Anglo-Saxons employed wergild – the "man-price" compensation – as the cornerstone of their legal systems. In Germanic custom, crimes were not solely offenses against the state but against families who demanded redress. Wergild provided a regulated alternative to blood feuds.

Social Gradations

Wergild reflected strict social hierarchies. In England: kings (30,000 thrymsas), ealdormen, thegns (1,200 shillings), and ceorls (200 shillings). In Frisia: nobilis (80 solidi), liber/freeman (40 solidi), and litus/half-free (20 solidi).

Oath-Helpers

Both systems used compurgation - oath-swearing backed by oath-helpers who vouched for character. The number required scaled with social rank and charge severity. A thegn needed fewer helpers than a ceorl for the same accusation.

Kinship and Feud

When compensation failed, both legal systems recognized blood feuds as legitimate. Anglo-Saxon law explicitly permitted a slain person's kindred to avenge death if wergild was unpaid, though kings and clergy promoted peaceful settlements.

Courts and Assemblies: Folkmoot and Terp Moot

Anglo-Saxon Courts

By the late Anglo-Saxon period, England had organized local courts called moots. Shire courts met twice yearly (Easter and Michaelmas), presided over by ealdormen and bishops representing royal and church authority. Hundred courts handled local disputes monthly.

These officials did not determine verdicts - the assembled freemen acted as judges, drawing on customary law and local precedent. This system provided unified royal oversight while preserving community participation in justice.

Frisian Assemblies

In Frisia, where royal officials were often absent, justice fell to local assemblies reminiscent of the old Germanic "thing." Villages held moots on <a href="/frl/skiednis/terpen" class="text-decoration-none">terpen</a> - man-made dwelling mounds - that served as natural amphitheaters for legal proceedings.

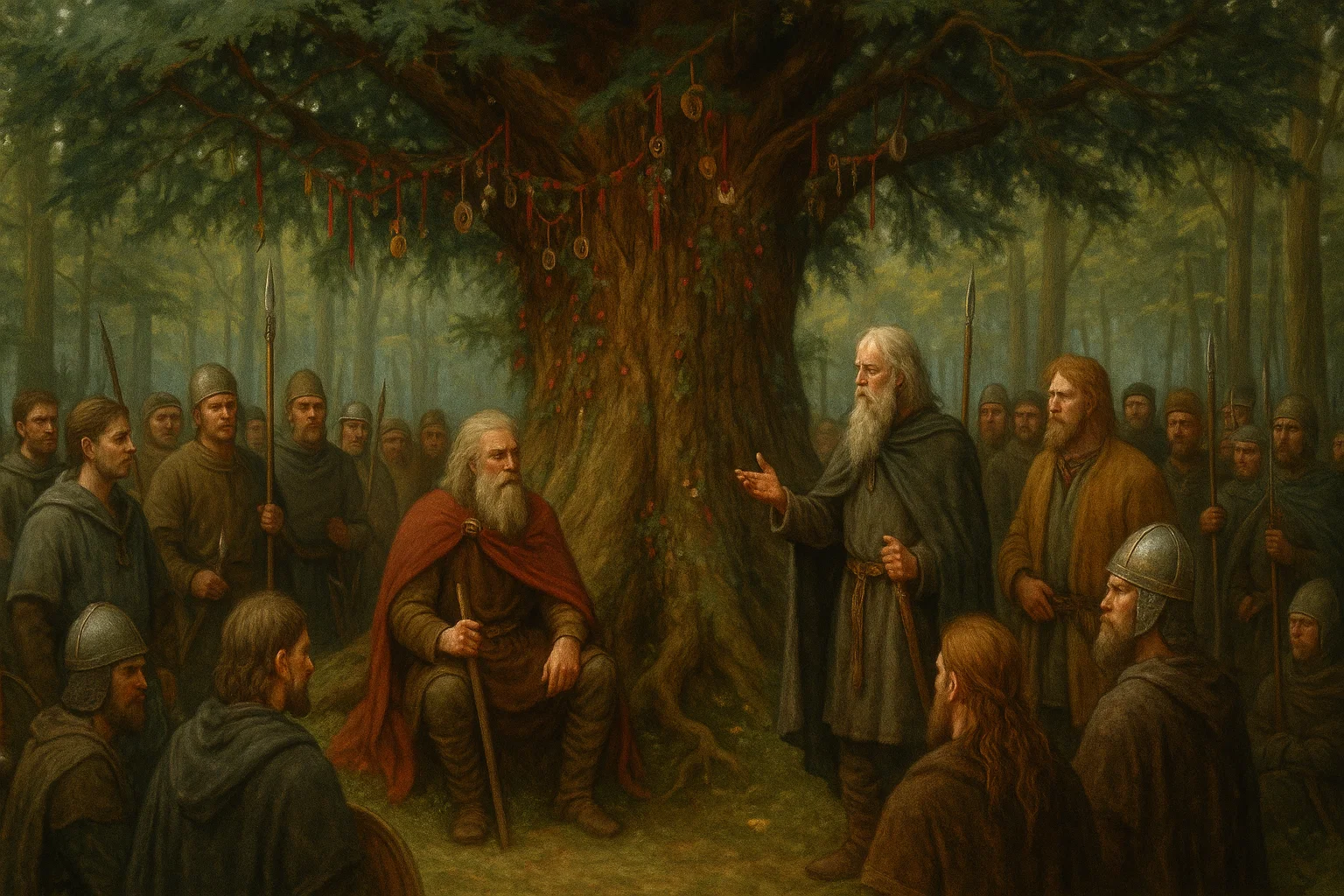

The famous Upstalsboom assemblies near Aurich represented the closest Frisia came to unified governance, where representatives from across Frisian lands gathered under an ancient oak to discuss common law and settle inter-regional disputes.

Frisian representatives gathering at the Upstalsboom assembly near Aurich, where delegates from across Frisian lands met under the ancient oak to discuss common law and settle inter-regional disputes

Both societies cherished certain procedural rights. Accusers made oath-backed claims, defendants could deny and choose proof by oath or ordeal. The Lex Frisionum mandated oath-helpers, while Anglo-Saxon law allowed defendants to select their preferred method of proof based on their social status.

Paths of Legal Development: Royal Innovation vs Local Autonomy

Anglo-Saxon Administrative Innovation

English kings developed sophisticated administrative systems early. Royal writs - written commands issued by the king - standardized legal procedures across the kingdom. This bureaucratic innovation allowed uniform justice administration from Cornwall to Northumberland.

Alfred's law code synthesized Kentish, Mercian, and West Saxon customs into a unified system. His successors built upon this foundation, creating the institutional framework that would evolve into medieval common law and ultimately influence constitutional developments like Magna Carta (1215).

Frisian Decentralized Freedom

Frisia experienced extensive decentralization. After Carolingian collapse (c. 1000), coastal Frisian regions functioned as autonomous farmer republics. Each terp community governed itself through assemblies, maintaining the ancient Germanic "thing" tradition in its purest form.

This approach solved immediate problems by preserving local customs and individual freedoms, but created different long-term challenges. Without royal writs or standardized procedures, legal decisions remained purely local, making coordinated responses to external threats increasingly difficult. The Lex Frisionum gradually transformed from a living legal framework into a cultural symbol - honored in memory but ineffective for addressing the realities of a changing medieval world.

Christianity played different roles in each system. Anglo-Saxon England integrated Christian clergy into royal administration - bishops co-presided over shire courts and helped develop written law. Frisian Christianity remained more autonomous, with local priests serving communities but not participating in royal governance, partly because there was no consistent royal authority to serve.

Divergent Paths: Frisian Feud vs English Monarchy

By the Late Middle Ages (14th–15th centuries), Frisia and England had evolved in opposite directions. Frisia, clinging to its freedom, descended into civil war, while England moved toward centralized monarchy and unified law.

English Centralization

England experienced its share of conflicts - the Peasants' Revolt (1381), baronial wars, and the Wars of the Roses (1455-1485) - but within a kingdom with enduring central government. After 1066, the monarchy became one of Europe's most centralized.

Royal common law courts gradually replaced local folk courts. By 1300, shire and hundred courts still existed but increasingly deferred to royal justice. This created stability and unified legal precedent across the kingdom.

Frisian Civil War (1350-1498)

Medieval Frisia fractured into opposing factions: the Vetkopers ("fat-buyers" - wealthy landowners) and Schieringers ("speakers" - those who preferred negotiation). This century-long civil war devastated the region and ultimately invited foreign intervention.

By 1498, the conflict had grown so destructive that the Schieringers secretly requested protection from Duke Albrecht III of Saxony. This ended Frisian freedom forever - the very insistence on local autonomy prevented forming higher authority, allowing foreign rulers to step in.

A reconstruction of a late medieval Frisian village during the Vetkopers-Schieringers civil war. The fortified stone towers (burgen) became essential for wealthy hoofdelingen families to protect themselves from constant feuding, transforming the peaceful farming landscape into a militarized countryside of competing strongholds.

During the 14th-15th centuries, the ideal of Frisian Freedom became paradoxically violent. Wealthy farming families built fortified stone towers called "burgen" or "states" to protect their holdings from rival factions. These defensive structures dotted the landscape, each representing a hoofdeling family's attempt to maintain independence through force. The proliferation of private fortifications showed how the absence of central authority, initially a source of freedom, ultimately drove communities to militarize for survival.

Legacy and Cultural Connections

Were there cultural links between Frisians and English that influenced later rebellious movements? While no direct line connects Frisian freedom to events like the Peasants' Revolt of 1381 or the English Civil War, both peoples shared an inherited ethos valuing freedom and local rights.

Linguistic Kinship

Frisian remains the West Germanic language closest to English. Old English and Old Frisian were virtually cousins, both descended from North Sea Germanic tribes. Anglo-Saxon settlers in 5th-6th century Britain included people from Frisian coastal areas.

Shared Legal Concepts

Both traditions preserved concepts like wergild, folk-moot, and friborh (peace-pledge) that emphasized community responsibility and local governance. These ideas persisted in English common law even as royal authority expanded.

Dutch Republic Influence

A more direct legacy appeared in the Dutch Revolt (late 16th century). Frisian representatives in the States General insisted on provincial sovereignty under the confederal system, drawing on centuries of self-government traditions rooted in the Lex Frisionum.

By the late Middle Ages, Frisia's decentralized freedom had created a systematic challenge: the very principles that protected local autonomy made collective action nearly impossible. While England's centralized authority could mobilize resources and coordinate responses to threats, Frisian communities remained locked in their traditional assembly system even as the medieval world around them grew more interconnected and militarized. Some historians have described the 15th-century conflicts as "Freedom's death by its confirmation" - the insistence on preserving local independence ultimately made that independence unsustainable.

The sword of Grutte Pier (Pier Gerlofs Donia, 1480-1520), the legendary Frisian freedom fighter who embodied the final heroic stand of Frisian independence against Habsburg rule

Pier Gerlofs Donia, known as Grutte Pier ("Big Pier"), represents the ultimate personification of Frisian Freedom's death throes. Standing over seven feet tall and wielding this massive two-handed sword, he led the last great rebellion against foreign rule (1515-1519). After Saxon oppression ended the medieval Frisian Freedom in 1498, and Habsburg forces subsequently occupied Friesland, Pier embodied the ancient Frisian spirit of resistance in physical form.

His guerrilla naval campaign in the Zuiderzee captured over 100 enemy vessels, proving that even after institutional freedom died, the Frisian ethos of independence lived on in individual heroism. Grutte Pier became the bridge between medieval Frisian Freedom and modern Frisian identity - transforming from legal and political autonomy into legendary resistance and cultural memory.

The cultural piracy tradition suggests remarkable Anglo-Frisian parallels spanning centuries. Grutte Pier's guerrilla naval warfare (1515-1519) and Francis Drake's privateering (1570s-1590s) both embodied similar North Sea maritime traditions - independence, resistance to continental powers, and the sea as pathway to freedom. Both men became national heroes for using ships to challenge imperial dominance.

This maritime resistance tradition stretches back to their shared Germanic ancestors - the same Frisian and Anglo-Saxon seafarers who raided Roman coasts and established kingdoms across the North Sea. The cultural DNA of seaborne independence, forged in Migration Period longboats, lived on through medieval Frisian naval raids and Elizabethan sea dogs. Both cultures instinctively turned to the sea when continental authority threatened their freedom.

Germanic Legal Concepts and Enlightenment Thought

Medieval Germanic legal traditions, including both Anglo-Saxon and Frisian concepts, were preserved and studied by Dutch scholars who became influential across 17th-18th century Europe. This scholarly transmission created pathways for early democratic principles to influence Enlightenment political theory and constitutional development, though the extent of direct influence remains debated among historians.

Universities in the Lowlands and Legal Scholarship

Universities at Leiden (1575), Franeker (1585) in Friesland, and Utrecht (1636) attracted international students seeking advanced legal education. Between 1650-1750, over 1,500 Scottish students attended universities in the lowlands, along with significant numbers from Germany, France, and Scandinavia. This academic exchange created intellectual pipelines between medieval legal traditions and Enlightenment thought.

Scholarly Synthesis

Scholars in the lowlands like Hugo Grotius, Frisian jurist Ulrik Huber, and Johannes Voet combined Roman law with Germanic customary traditions, creating "legal humanism" that emphasized natural law principles and constitutional limitations. While direct connections to early medieval sources are often unclear, this approach provided theoretical frameworks that influenced constitutional development across Europe.

Scottish Legal Innovation

Scholars educated in the lowlands returned home with pedagogical practices and legal concepts that transformed Scottish universities and law. Unlike the English system of overlapping jurisdictions, Scotland developed a hierarchical, appellate judiciary with constitutional protections—features that echo both Roman law training and Germanic assembly traditions preserved in Frisian legal education.

Constitutional Legacy

The Scottish legal system's unique features—separation from English law, hierarchical courts, and constitutional framework—influenced the American framers. Scottish Enlightenment thinkers like Hume shaped the Declaration of Independence's "self-evident truths," while the Scottish judicial model contributed to Article III of the Constitution. Through this pathway, Germanic legal concepts studied in universities in the lowlands may have contributed to constitutional development in the New World.

Frisian Legal Humanism

The University of Franeker in Friesland contributed to a broader tradition of "legal humanism" that combined Roman law scholarship with Germanic customary law. This synthesis, developed by Frisian jurists like Ulrik Huber, created a distinctive approach that emphasized natural law principles and constitutional limitations on authority. Universities in the lowlands became centers for this innovative legal scholarship that attracted students across Europe.

International Influence

The Dutch Republic's tolerance and intellectual freedom made it a haven for radical ideas. French philosophes like Montesquieu studied Dutch constitutional arrangements and separation of powers concepts. The Dutch tradition of balancing local autonomy with federal coordination provided models that influenced both the American framers and French revolutionary thinkers seeking alternatives to absolute monarchy.

French Revolutionary Impact

Montesquieu's "Spirit of the Laws" (1748), influenced by Dutch constitutional theory, became the most quoted authority in pre-revolutionary America and shaped the French Declaration of Rights (1789). The concept of separation of powers—executive, legislative, judicial—reflected Germanic assembly traditions filtered through Dutch legal scholarship and Enlightenment rationalism.

Revolutionary Legacy

The French Revolution's legal reforms—abolishing feudalism, establishing equality before law, codifying civil rights—drew on Enlightenment principles that had Germanic constitutional roots. Jefferson acknowledged deriving the Declaration of Independence from Rousseau, Locke, and Montesquieu, while the French revolutionaries explicitly cited these same thinkers in crafting their new legal order based on "Liberté, égalité, fraternité."

Intellectual Transmission

The transmission of legal concepts from medieval Germanic societies to Enlightenment constitutional thought occurred through multiple pathways - university education, manuscript preservation, legal scholarship, and parallel development of similar ideas in different contexts. While historians debate the extent of direct influence, the documented presence of over 1,500 Scottish students at universities in the lowlands during the critical 1650-1750 period suggests significant intellectual exchange occurred. The challenge lies in tracing which specific ideas traveled through these networks and which developed independently from similar starting points.

Two Paths from Common Roots

From shared Germanic origins emerged two remarkable legal experiments. Anglo-Saxon England pioneered early administrative sophistication - Æthelberht's Laws (602) predated continental legal codes, Alfred's synthesis created lasting institutional frameworks, and royal writs established procedures that evolved into common law and constitutional monarchy. The Anglo-Saxon synthesis of Germanic custom, Christian morality, and Roman administration proved remarkably durable.

Frisia experienced radical decentralization, maintaining extensive local autonomy through traditional Germanic assembly practices. Terp assemblies, the Upstalsboom gatherings, and the ideal of "Frisian Freedom" preserved individual liberty and local governance for centuries. Though this approach ultimately proved vulnerable to external conquest, it maintained constitutional traditions that influenced later developments in federal governance and concepts of local autonomy.

The extent to which these early medieval legal traditions directly influenced later constitutional development remains an area of scholarly investigation. What seems clear is that certain constitutional concepts—local assemblies, compensation-based justice, limitations on royal authority—appeared in various forms across Germanic societies and may have provided precedents that later legal scholars could reference. Whether through direct transmission or parallel development, the comparison reveals persistent tensions between centralized authority and local autonomy that continue to shape constitutional debate.

Related Articles

Early Medieval Trade Networks

Explore the commercial connections that linked Frisian and Anglo-Saxon societies across the North Sea, including the emporia of Dorestad and Hamwic.

Migration Period Longboats

Discover the seafaring technology that enabled both Frisian and Anglo-Saxon expansion and maintained their shared maritime culture.

Anglo-Saxon & Frisian Runes

Learn about the shared runic traditions that preserved legal and cultural knowledge in both societies.

Sources and Further Reading

Primary Sources

- Lex Frisionum (c. 790s) - Codification of Frisian customary law under Charlemagne

- Textus Roffensis - Collection of Anglo-Saxon law codes including Æthelberht's Laws

- Jancko Douwama's "Boeck der Partijen" (1505) - Chronicle of Frisian civil wars

- Karelsprivilege and other fabricated Frisian charters (1297-1319)

- Ulrik Huber's "Heedensdaegse Rechtsgeleertheyt" (1686) - Frisian legal traditions

Modern Scholarship

- Van der Tuuk, J. (1884) - "Friesche Geschiedenis" - Foundational study of Frisian law

- Liebermann, Felix (1903-1916) - "Die Gesetze der Angelsachsen" - Critical edition of Anglo-Saxon laws

- Hines, J. (1984) - "The Scandinavian Character of Anglian England" - Germanic legal traditions

- Wormald, Patrick (1999) - "The Making of English Law" - Anglo-Saxon legal development

- Nijdam, Han (2008) - "Lichaam, eer en recht in middeleeuws Friesland" - Frisian legal culture

- Sprunger, D. (2010) - "Franeker University and the Scottish Enlightenment" - Educational networks