Anglo-Saxon and Frisian Runes

The Futhorc Alphabet of Early Medieval Britain and Frisia

An exploration of the runic script that bridged the ancient Germanic world with early Christian literacy

The Anglo-Frisian Futhorc (also known as the Anglo-Saxon runes) was an early medieval runic alphabet used in Anglo-Saxon England and coastal Frisia. This script was a local adaptation of the older Elder Futhark, modified to suit the Old English and Old Frisian languages. From roughly the 5th to 11th centuries, the Futhorc was employed for inscriptions on objects ranging from jewelry and weapons to stones and wooden artifacts.

This article explores the origins of the Futhorc from its Elder Futhark ancestor, its distinctive features relative to other Germanic runic alphabets, notable inscriptions in both England and Frisia (like the famed Franks Casket and Ruthwell Cross), the varied uses of runes in daily life and ritual, and the eventual decline of runic writing with the rise of Latin literacy.

Origins: From Elder Futhark to Anglo-Frisian Futhorc

Runic writing was first developed by Germanic peoples around the mid-2nd century CE, with the Elder Futhark of 24 runes being the earliest known runic alphabet. The runes were likely inspired by Mediterranean alphabets (with Latin or Greek influences debated) and were designed to be carved into hard materials, featuring angular strokes for easy incising.

By the Migration Period (~5th century CE), the use of runes had spread widely across Germanic Europe. It was during this time that a branch of the runic tradition evolved into the Anglo-Frisian Futhorc as certain Germanic tribes (Angles, Saxons, Jutes, and Frisians) migrated and settled in Britain and the North Sea coast.

Why "Futhorc" instead of "Futhark"?

The term Futhorc comes from the first six rune names in the Anglo-Saxon sequence: Feoh, Ur, Þorn, Ōs, Rād, Cēn (ᚠ, ᚢ, ᚦ, ᚩ, ᚱ, ᚳ). The replacement of the fourth rune (Ansuz ᚨ for /a/) with Ōs ᚩ for /o/ is one of the notable evolutionary steps in the Anglo-Frisian system.

Linguistic Adaptations

As Anglo-Saxon settlers established themselves in Britain in the 5th century, they brought the runic script with them. In the new linguistic environment of Old English, the script underwent modifications. Old English (and similarly Old Frisian) had a more complex vowel system – including multiple diphthongs and new sounds – which the 24 letters of Elder Futhark could not adequately represent.

Scribes and carvers began adding new runes and altering old ones to accommodate these sounds. For example, runes for /a/, /æ/, /y/, and the diphthong /ea/ were introduced, known by names like Ac ᚪ (meaning "oak"), Æsc ᚫ ("ash"), Yr ᚣ, and Ear ᛠ. These additions expanded the original alphabet beyond the Elder Futhark's 24 characters. In total, the Anglo-Saxon rune set eventually grew to around 28–33 runes in various regional variants.

Distinctive Features and Differences from Other Runic Alphabets

The Anglo-Saxon/Frisian Futhorc can be contrasted with the other major runic alphabets of the early Middle Ages: primarily the Elder Futhark and the Younger Futhark. Several key differences stand out:

Size of the Alphabet

The Futhorc eventually used over two dozen runes (often 28, and up to 33 in some listings), whereas the Elder Futhark had 24 runes and the later Scandinavian Younger Futhark had only 16. This means Anglo-Frisian runic inscriptions could represent sounds (especially vowels) with greater precision.

Newly Invented Runes

The Anglo-Frisian runes include several innovations not found in Elder Futhark. Runes like ᛞ (Dæġ, for /d/) and ᛝ (Ing, for the /ŋ/ sound "ng") were modifications to address phonetic needs of Old English and Old Frisian that weren't present in Proto-Germanic.

Retention of Older Sounds

The Anglo-Saxon Futhorc preserved runes for sounds that in other regions fell out of use. Notably, the Þorn (Thorn) rune ᚦ for /th/ and ƿynn (Wynn) rune ᚹ for /w/ remained important in Anglo-Frisian usage and were later adopted into the Latin alphabet by Anglo-Saxon scribes.

Use on Different Media

In Anglo-Saxon England and Frisia, runic inscriptions are rarely on giant stones in the landscape; instead, they appear mostly on portable objects or small monuments. Runes are found on items like jewelry, weapons, tools, coins, amulets, as well as some stone crosses and building elements.

Notable Runic Inscriptions in Anglo-Saxon England and Frisia

Despite the relatively small corpus, a number of runic inscriptions from England and Frisia stand out for their length, artistry, or cultural significance. These inscriptions provide a window into how Futhorc runes were actually used by early medieval people.

Anglo-Saxon England: Franks Casket, Ruthwell Cross, and Other Treasures

The Franks Casket

The Franks Casket (8th century) - whale bone carved with runic inscriptions and scenes from Germanic legend, Roman history, and Christian narrative

One of the most famous artifacts bearing Anglo-Saxon runes is the Franks Casket. Dating to the early 8th century (likely ca. 700–720 CE), this small box is carved from whale's bone and covered in intricate scenes with accompanying inscriptions. The casket depicts a fascinating mix of imagery: episodes from Germanic legend, Roman history/mythology, and a scene from the New Testament.

The longest continuous text on the Franks Casket is a riddling alliterative verse in Old English carved around the front panel. It describes the making of the casket itself in a poetic way, referring to the whale bone material. The carver was evidently literate in both Latin and Old English, choosing runes at times perhaps to evoke an archaic or esoteric feel.

The Ruthwell Cross

The Ruthwell Cross (8th century) - detail showing Christ with runic inscriptions from The Dream of the Rood poem running vertically along the vine-scroll borders

Another renowned Anglo-Saxon runic monument is the Ruthwell Cross, an 8th-century stone cross located in present-day Scotland (historically Northumbria). This towering sandstone cross (about 5.2 meters tall) is richly carved with vines and Christian imagery, and it bears inscriptions in two scripts: Latin (using the Roman alphabet) and Old English (using runes).

On the narrow sides of the cross, lines of runic text run vertically amidst the vine-scrolls. These runes famously record part of an Old English religious poem, The Dream of the Rood, making it one of the earliest known texts of English poetry. About 18 verses of the poem are inscribed in runes on the Ruthwell Cross.

The use of runic lettering for a Christian poem suggests the carvers wanted this message to be legible to an Anglo-Saxon audience familiar with runes rather than to clergy trained only in Latin.

Other Anglo-Saxon Runic Finds

The Thames Scramasax (Seax of Beagnoth, 9th century) - showing the complete 28-rune Futhorc alphabet engraved on the blade followed by the owner's name

- Personal items and jewelry: A number of brooches, sword pommels, and rings from 6th–7th century England bear short runic texts. The Thames scramasax (also called the Seax of Beagnoth, 9th century) carries the entire alphabet of 28 runes engraved on its blade, followed by the name Beagnoth.

- Funerary urns and memorials: Early Anglo-Saxon cremation urns sometimes have runic "labels" or charms. At the Spong Hill cemetery in Norfolk (5th century), at least three urns were stamped with identical runic sequences spelling "alu" – thought to mean "ale" or a magical term for protection/fertility.

- Literary inscriptions: The Old English Rune Poem (recorded in a 10th-century manuscript) is essentially a didactic poem listing the runes and explaining their meaning in alliterative verse, showing that knowledge of the runes survived in learned circles even after they fell out of common use.

Frisia: Runic Combs, Coins, and Wood Finds

The Frisian branch of the Anglo-Frisian runic tradition is lesser-known but equally intriguing. Frisia (the coastal regions of what is now the Netherlands and Germany) was closely connected to Anglo-Saxon England in the early Middle Ages through trade and migration, and the runic inscriptions found there use essentially the same Futhorc alphabet.

Bone Combs and Cases

Frisians often inscribed grooming tools. A bone comb case from Kantens (Groningen, Netherlands), dated to the early 5th century, is the earliest runic find in Frisian territory. The Oostum comb from the 8th century has an inscription that might include the word for "comb" (kambu) and a personal name.

Wooden Staves and Sticks

The longest Frisian runic inscription known is on the Westeremden Yew-stick, a yew wood stick found in Groningen and dated to the 8th century. It carries a lengthy sequence of runes in three lines, demonstrating that runes were not confined to one-word names in Frisia.

Runic Coins

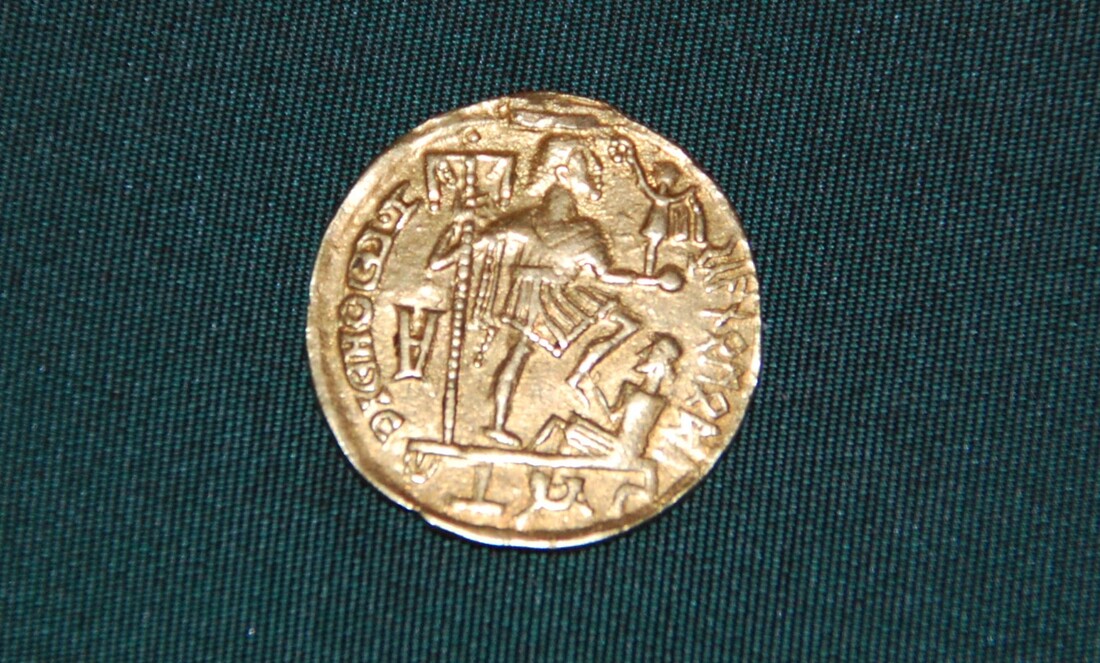

Skanomodu solidus (c. 575–610 AD)

Frisia has yielded a few early medieval coins with runic legends. The "Skanomodu" solidus (c. 575–610 AD) inscribed with the runes "skanomodu" is thought to be a name, possibly of a moneyer or leader. These coins show runes were prestigious enough to appear on currency.

Additional Frisian Artifacts

The Arum "sword" (late 8th century) - a small yew-wood ritual sword inscribed with "edaþboda" (possibly a name, Edaþ-boda)

A few additional Frisian finds include the Arum "sword" (actually a small yew-wood ritual sword, late 8th century) inscribed "edaþboda" (perhaps a name, Edaþ-boda); a whalebone sword hilt from Rasquert with the runic text "ek umaëdit oka" interpreted as "I, Oka, [not] mad [made]" or some kind of boast; and the Bernsterburen staff (c. 8th century) with a line in runes. Each of these is fragmentary in its own way, but collectively they indicate that Old Frisian was being written in runes by local craftsmen or elites.

Uses and Functions of Runes in Daily Life

Anglo-Saxon and Frisian runes served various practical, ceremonial, and artistic purposes throughout their period of use. Understanding these functions helps us appreciate how integrated runic literacy was in early medieval society.

Runes were commonly used for practical purposes such as:

- Craftsmen signing their work on brooches, weapons, and tools

- Ownership marks on personal belongings like combs and jewelry

- Names and titles on coins and currency

- Labels and identifiers on everyday objects

These uses show runes functioning as a normal writing system for commerce and identification, rather than just ceremonial purposes.

Runes also served important ceremonial and religious functions:

- Protective charms on funerary urns (like the "alu" inscriptions)

- Christian poetry and biblical references (as on the Ruthwell Cross)

- Memorial inscriptions commemorating the dead

- Sacred objects like St. Cuthbert's coffin with runic inscriptions naming evangelists

The transition from pagan to Christian uses demonstrates the adaptability of the runic script across religious boundaries.

Runes also served as a medium for artistic and literary expression:

- Riddling verses like those on the Franks Casket

- Poetry transcription (excerpts from The Dream of the Rood)

- Alliterative and formulaic inscriptions

- Display of linguistic virtuosity by mixing scripts and languages

These artistic uses show that runic literacy extended beyond basic functionality to sophisticated literary culture.

Decline and Legacy of the Futhorc

The Anglo-Saxon and Frisian runic tradition gradually declined between the 8th and 11th centuries, coinciding with the spread of Christianity and Latin literacy. However, this decline was not a sudden suppression but rather a gradual cultural shift.

Factors in Decline

- Rise of Latin literacy through Christian education

- Church preference for Latin script in official documents

- Gradual shift from oral to written culture

- Loss of traditional Germanic cultural practices

Lasting Influence

- Þorn (þ) and Wynn (ƿ) letters adopted into Latin script

- References in Old English literature and manuscripts

- Preservation in antiquarian works like the Rune Poem

- Modern archaeological and scholarly interest

A Peaceful Transition

Unlike popular misconceptions, there is little evidence of active Christian suppression of runes. Instead, the decline appears to be a natural cultural evolution as Latin literacy became more prestigious and practical for an increasingly Christianized society.

Conclusion

The Anglo-Saxon and Frisian Futhorc represents a fascinating chapter in the history of writing systems. Born from the ancient Elder Futhark tradition but adapted to serve the unique linguistic needs of Old English and Old Frisian, this expanded runic alphabet demonstrates the creativity and adaptability of early medieval scribes and craftsmen.

From practical ownership marks on everyday objects to sophisticated literary works like The Dream of the Rood, the Futhorc served multiple functions in Anglo-Frisian society. Its eventual decline in favor of Latin script marks not just a change in writing systems, but a broader cultural transformation as the North Sea world transitioned from its Germanic tribal origins to medieval Christian kingdoms.

Today, the artifacts bearing Anglo-Saxon and Frisian runes – displayed in museums like the British Museum (Franks Casket) and still standing in places like the Ruthwell Cross – serve as tangible links to this remarkable period when ancient Germanic traditions met the emerging Christian world, creating something entirely new in the process.

References and Sources

Academic Sources

This article is based on scholarly research from runologists, archaeologists, and historians specializing in early medieval Germanic writing systems. All claims are grounded in archaeological and academic evidence.

-

Page, R.I. An Introduction to English Runes. 2nd ed., Boydell, 1999.

The definitive authority on Anglo-Saxon runes. Page's work underpins much of the factual content regarding inscriptions, dating, and interpretation. -

Looijenga, Tineke. Runes Around the North Sea and on the Continent AD 150–700. Dissertation, University of Groningen, 1997.

Key academic work on Anglo-Frisian runes, discussing the Frisian corpus of runic finds and their archaeological context. -

Findell, Martin & Kopár, Lilla "Runes and Commemoration in Anglo-Saxon England." Fragments (Univ. of Michigan) vol.6, 2017.

Analyzes the use of runes on commemorative objects and the interplay of text and object in early medieval England.

-

British Museum Online Collection - Franks Casket

Descriptive entry for the Franks Casket, confirming the runic whale-bone riddle inscription and the mix of scenes. -

University of Oxford - The Ruthwell Cross

Background on the cross, confirming that its runes correspond to The Dream of the Rood and describing its artistic significance. -

World History Encyclopedia - Runes by Emma Groeneveld, 2018

Overview of runic alphabets, including the Elder Futhark, Anglo-Saxon Futhorc, and Younger Futhark, with historical context.

-

Johannes Beers - "Runes in Frisia" and "The Corpus of Frisian Runic Inscriptions"

Provides detailed analysis of Frisian runic finds and emphasizes that the church did not actively ban runes. Cites scholarly works like Looijenga 1997 and Quak 1990. -

Archaeological Journals - Hines, John (2015) and Oosting, Reider (2021)

Specialist sources on runic inscriptions in early England and Frisian runic finds, informing interpretations of specific inscriptions. -

The Old English Rune Poem - Various scholarly editions

Surviving text providing cultural context for runic symbolism and the meanings attached to individual runes in Anglo-Saxon tradition.

Note on Scholarly Consensus

Where interpretations are uncertain (such as the meaning of specific inscriptions or the timing of runic additions), scholarly opinions vary and this has been noted throughout the article. The goal has been to rely on academic and museum sources to ensure the information presented about the Futhorc alphabet is reliable and up-to-date.