Early Medieval Trade between Anglo-Saxon England and Frisia

Between the 7th and 9th centuries, a flourishing network of trading ports called emporia connected Anglo-Saxon England and Frisia across the North Sea. These bustling maritime centers facilitated exchange of everything from everyday goods to luxury items, creating cultural and economic bonds that would shape both regions.

Trade routes connecting major emporia of the North Sea world

Contents

The Rise of Emporia: Anglo-Saxon and Frisian Trading Ports

Dorestad, located at the Rhine delta in what is now the Netherlands, rose to prominence in the 7th–9th centuries as "the biggest shipping hub of north-western Europe." Its strategic location at the junction of Rhine trade routes and the North Sea made it a clearing-house between the Frankish interior and the North Sea world.

By the 8th century, Dorestad had grown into a populous emporium with an estimated 2,000-3,000 inhabitants and wharves stretching a kilometer along the river. It thrived under Frankish control after 719, even minting its own coins under Charlemagne and his successors.

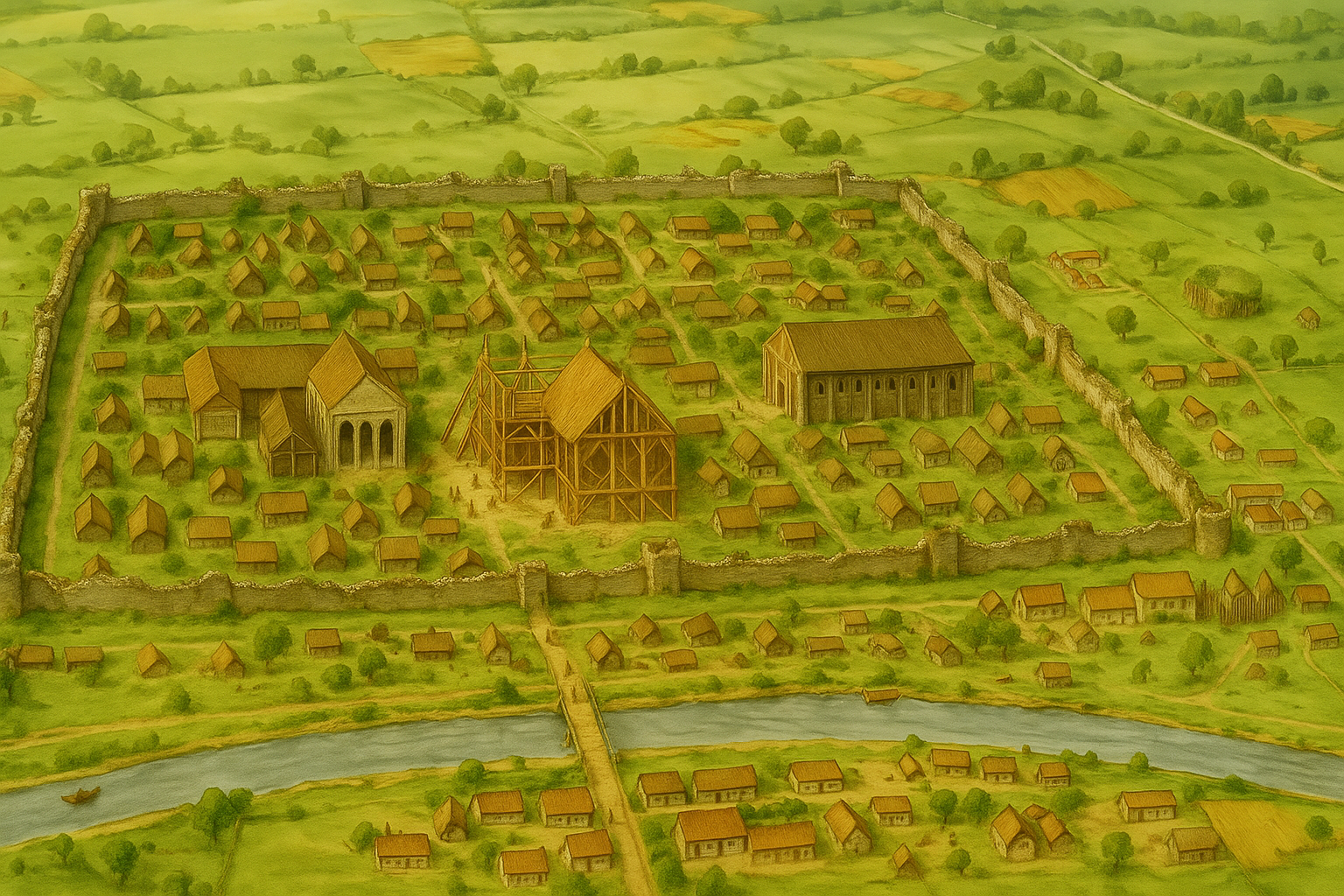

Reconstruction of Dorestad, the greatest shipping hub of northwest Europe

- Wine from Frankish Gaul (archaeologists found wine barrels from Mainz)

- Lava quern-stones for grinding grain

- Fine glassware from the Rhineland

- Lead and tin from English mines

- Woollen textiles from Britain

Renowned as a "vicus famosus" (famous town), Dorestad was essentially an open market-town with minimal fortifications, operating as neutral ground for Frisians and Franks alike. The 8th-century poet Alcuin even referenced it as "Dorstada" in plural, hinting at its dual towns or quarters.

The Unique Morphology of Dorestad

Dorestad's layout was uniquely adapted to its wetland environment. Long wooden jetties extended into the Rhine, built progressively longer over time as the river course shifted and silted. The settlement's timber-framed longhouses were raised on poles above the flood-prone peatland, protecting inhabitants and goods from seasonal high waters.

Dorestad's distinctive stilt houses and extended jetties adapted to the changing Rhine course

Behind the commercial waterfront lay extensive pastures supporting sheep and cattle on the rich peatland soils. This integration of maritime commerce with pastoral agriculture created a distinctive landscape that can still be glimpsed today in places like Giethoorn in the eastern Netherlands and Earnewâld in Fryslân, where traditional pole-supported houses and waterway-centered settlement patterns echo Dorestad's medieval design.

Across the sea in Wessex, Hamwic grew into a primary English emporium around the year 700. Situated on the River Itchen near the Solent, Hamwic covered at least 40–45 hectares at its height.

Excavations at Hamwic's "Six Dials" area reveal a planned town layout: a grid of gravel streets, property plots with timber buildings and workshops, all enclosed by a perimeter ditch. This degree of planning suggests royal involvement in its foundation as a deliberate trading center for the Kingdom of Wessex.

Aerial reconstruction showing Hamwic's planned street grid and timber buildings

- Metal smiths, leather tanners, bone and antler carvers

- Textile spinners and weavers

- 18 percent of pottery imported from northern France

- Rhenish Tating ware (fine ceramic pitchers)

- Over 180 early medieval coins found

By the late 9th century, Hamwic was in decline and largely abandoned after Viking attacks. Its functions shifted to the nearby fortified town of Winchester for safety.

Ipswich (Old English Gipeswic), in the kingdom of East Anglia, was founded in the 7th century (c. 625) and became noteworthy as a center of production as well as trade.

Ipswich potters pioneered the first wheel-turned, kiln-fired pottery in England since Roman times – a distinctive gray ware known as Ipswich Ware, mass-produced in the town and distributed widely across eastern England.

By the 8th century, Ipswich had become renowned for pottery manufacture and as one of the earliest centers for wool export. East Anglia's sheep-rich estates produced wool and textiles that were shipped via Ipswich to cloth-hungry markets abroad.

Unlike other emporia, Ipswich continued into the 9th century and, despite disruptions during Viking incursions when the Great Army occupied East Anglia in the 860s, it evolved into a medieval town that persisted under later Danish and English rule.

In the north, York served as Northumbria's principal commercial center. Although York was a former Roman city (Eboracum) and the seat of an archbishopric, in the 7th–8th centuries part of it functioned similarly to the wics.

York (Eoforwic) in the 8th century, showing the fortified city with its early stone church under construction (later the site of York Minster) and river trading access

Early medieval records note Frisian traders active in York (called Eoforwic in Old English). Frisian merchants accessed the resources of the Northumbrian hinterland, including hides, wool, and notably slaves – a grim but significant trade of the era.

Archaeological evidence shows imported items like continental wine barrels, glassware, and Baltic amber making their way to Northumbria. York's role grew even larger after 867, when Viking armies conquered the city, transforming it into Jórvik, a Viking-ruled emporium integrated into the Scandinavian trade network.

The Frisian Emporium Model: Template for Northern Europe

The success of Frisian emporia didn't go unnoticed. Across the North Sea and Baltic regions, new trading centers emerged that consciously adopted Frisian marketplace innovations, creating a network of interconnected commercial hubs that transformed medieval trade.

Hedeby's rise around 804 AD exemplifies how Frisian trading expertise spread northward. Located just 100 kilometers southeast of the established Frisian emporium at Ribe, Hedeby's founders appear to have used nearby Frisian markets as direct templates for creating their own successful trading center.

The Hedeby archaeological site today, showing the peaceful landscape where one of medieval Europe's greatest trading centers once bustled with Frisian, Danish, and international merchants

Ribe was established as a seasonal Frisian marketplace by around 700 AD, becoming Scandinavia's oldest town. For over a century, it served as the primary model for how a successful North Sea trading center should operate, directly influencing Hedeby's later development.

Copied Innovations: From Street Grids to Silver Standards

Hedeby's archaeological record reveals systematic adoption of Frisian commercial practices. The settlement featured planned street grids and waterfront quays optimized for cargo handling, directly mirroring layouts first perfected at Ribe and other Frisian emporia.

More significantly, Hedeby adopted the Frisian concept of a neutral 'wic' – an open, unfortified trading zone under royal protection where merchants enjoyed broad freedoms. Even the precise 1.3-gram sceatta silver standard developed in Frisian markets was adopted wholesale at Hedeby.

Frisian Merchants as Cultural Bridges

Frisian merchants were among Hedeby's first settlers, establishing their own quarter alongside Danes and Angles. This diaspora carried not just goods but business methods, lending Hedeby an instantly cosmopolitan character that echoed the multicultural atmosphere of earlier Frisian emporia.

By the mid-9th century, Hedeby had grown to dominate the region, eclipsing Ribe's earlier preeminence while building directly on its commercial foundation. The student had become the master, but the Frisian blueprint remained clearly visible in Hedeby's structure and success.

Commodities of Cross-Channel Trade

Trade between Anglo-Saxon England and Frisia featured a mix of luxury goods for elites and bulk staples and raw materials. Early commerce focused on high-value, low-bulk prestige goods, but as the 8th century progressed, merchants increasingly handled everyday commodities in bulk.

Textiles and Wool

Cloth was one of the most important exports. England and Frisia both produced woolen textiles; East Anglia exported raw wool via Ipswich. Frisia was famed for its "pallium Fresonicum" or Frisian broadcloth, highly sought after across Europe.

Metals

England's mineral resources made it a supplier of lead and tin from British mines, exported through ports like Hamwic and Dorestad. Lead was used for roofing and pipes, while tin from Cornwall was vital for making bronze.

Amber and Ivory

Amber from the Baltic coasts was prized for beads and ornaments. Frisian merchants obtained amber and sold it in England and Francia. This precious fossilized resin continues to wash up on Frisian shores to this day, maintaining an unbroken connection to ancient trade routes. Walrus ivory from Arctic Scandinavia also entered the market via Norse and Frisian traders.

Wine, Oil, and Foodstuffs

Wine from Frankish Rhine and Meuse vineyards was imported to England via Dorestad. In return, England sent agricultural produce: surplus grain, preserved meat, cheese, and salt from coastal salt pans.

Complete Trade Inventory

One contemporary list of goods in Frisian trade includes: "hides and leather, bone, wool, cloth, cheese, butter, flax and linen, jewelry, pottery (including fine Tating ware), glassware, weapons, spices, walnuts, raisins, olive oil, gold brocade, Chinese silk, exotic shells, beads, wine, quern stones, whetstones, furs, walrus ivory, amber, grain, dried fish, combs, and slaves."

Ships, Markets, and Money: How Trade Was Conducted

Nautical Innovations – Ships and Navigation

The Frisians were renowned as the maritime carriers of the early Middle Ages – so much so that the North Sea was dubbed "Mare Fresicum" (Frisian Sea) by some writers. Frisian-built ships were typically clinker-constructed wooden sailing vessels, sturdy enough for North Sea voyages. Learn more about Migration Period longboats.

Early medieval trading vessel, similar to those used by Frisian merchants in the 7th-9th centuries

During the 7th–9th centuries, Frisian merchants used clinker-built sailing vessels adapted from earlier migration period designs. These sturdy ships could carry cargo safely across North Sea routes, with a favorable wind enabling crossings from the Rhine mouth to eastern England (200+ km) in just 2 days. The famous flat-bottomed cog would later be developed by Frisian shipwrights, but not until the 12th century.

Market Structures and Legal Frameworks

The emporia were usually royally sanctioned markets. Anglo-Saxon kings realized that concentrating trade in designated wics allowed them to regulate and tax commerce. At places like London, kings charged tolls on goods traded, and traders at a wic enjoyed the king's protection.

Coinage – Sceattas and Pennies

By the late 600s, Anglo-Saxon and Frisian mints began producing small silver coins known as sceattas. These were typically around 1.2–1.3 grams of silver – small enough in value to be useful for everyday trade.

Frisian sceatta showing detailed runic inscription and cross design typical of early medieval coinage

About 3,000 Frisian sceattas have been found in England, indicating how common Frisian currency was in Anglo-Saxon markets. The flow was mostly one-way – Frisian coins went abroad to pay for imports, whereas Anglo-Saxon coins rarely circulated in Frisia.

Archaeological Evidence of Anglo-Frisian Trade

Archaeology has richly corroborated the historical picture of Anglo-Saxon and Frisian trade. The port-emporia have yielded abundant imported goods, coin hoards, and specialized tools that testify to long-distance connections.

Imported Pottery

Distinctive continental ceramics like Tating ware (fine red-slipped pottery) and Rhenish blackware appear in English sites. These likely came filled with Frankish wine or oil, direct signs of commerce.

Coin Hoards

Thousands of silver sceattas found across emporia sites show the volume of monetary exchange. Coin-loss analysis at Hamwic shows a dramatic start in the early 8th century, peaking mid-century.

Trade Tools

Balance scales, weights, and merchant tools found at emporia indicate sophisticated commerce. Bronze weights stamped with designs, bone styli for record-keeping, and precise measuring instruments.

Manufacturing Evidence

The emporia show evidence of production for trade: iron slag and crucibles at Hamwic indicate metalworking; cattle bones with cut marks at Ipswich show leather tanning; vast quantities of deer antler at York and Hamwic reveal comb-making industries. The spread of Ipswich ware pottery across England and to Frankish coasts proves mass production for export.

Cultural and Linguistic Exchange through Commerce

Trade was not only economic but also a conduit of culture and ideas. The constant movement of merchants, sailors, and craftsmen across the North Sea transmitted languages, technologies, artistic styles, and beliefs in both directions.

Linguistic Cousins – Easy Communication

Old English and Old Frisian were so similar that they were likely mutually intelligible in the early Middle Ages. They belonged to the "Anglo-Frisian" subgroup of Germanic languages, which meant a Frisian trader could converse with an Anglo-Saxon with relative ease. Explore their shared Anglo-Frisian origins.

An Old Frisian trader might call a ship a "skip" (as did an Old English speaker), and count coin "scillings" in both languages. Maritime terms often spread between the languages, and place-names show cross-fertilization. See how this shared heritage appears in runic inscriptions.

Spread of Skills and Styles

Trade carried technologies and fashions. The introduction of wheel-turned, kiln-fired pottery in England (Ipswich Ware) was almost certainly due to continental influence. Glassmaking, lost in post-Roman Britain, saw revival through contact with Frankish centers.

Artistic motifs like animal-interlace designs were carried on portable items through trade. Frisian coinage features designs that likely originated from Anglo-Saxon motifs, and runic inscriptions appear on coins found on both sides of the sea.

Diaspora Communities and Multicultural Ports

The ports became melting pots of different peoples. Frisian quarters existed in York, Hedeby, and London by the 7th century. These expatriate merchants brought their customs and religion, creating polyglot atmospheres where Latin, Old Saxon, Frankish, Norse, and British Celtic languages could be heard. This cultural mixing influenced Anglo-Frisian mythology and beliefs.

Decline and Transformation (9th–10th Centuries)

By the mid-9th century, the vibrant trading system that linked Anglo-Saxon England and Frisia began to falter. A combination of political upheavals, Viking depredations, and evolving economic structures led to the decline of the classic emporia network.

Viking Raids and Instability

The 830s saw the first major Viking attacks on Frisian coasts. In 834, Vikings raided Dorestad, and although not utterly destroyed, it never fully recovered. Repeated raids between 834 and 839 disrupted trade severely.

Economic Transformation

The Carolingian Empire's shift toward overland trade routes and the rise of fortified burhs in England changed trade patterns. Commerce moved from open emporia to protected town markets, altering the medieval commercial landscape.

Legacy of Anglo-Frisian Trade

Though the classic emporia declined, the Anglo-Frisian trade network had lasting effects: it established monetary economies, created international trade laws, spread technologies and artistic styles, and forged cultural connections that would influence medieval Europe. So dominant were Frisian merchants that "Frisian" became synonymous with "trader" across much of northern Europe – a testament to their commercial prowess and reach.

The network's infrastructure and relationships provided the foundation for the later Hanseatic League trade routes. The centuries-established Frisian trading networks, with their proven sea routes, established ports, and commercial practices, became the backbone upon which the Hanseatic merchants would build their medieval trading empire. In this way, the early medieval Frisian traders were not just participants in commerce – they were the architects of Northern European trade.

The Maritime Bridge of Medieval Europe

The early medieval trade network between Anglo-Saxon England and Frisia was more than economic exchange – it was a cultural bridge that connected the North Sea world. Through bustling emporia like Dorestad, Hamwic, and Ipswich, merchants traded everything from everyday wool and wine to exotic amber and silk, creating prosperity and cultural fusion.

The shared language heritage, innovative ship technology, and standardized coinage of this trade network established patterns that would influence European commerce for centuries. Though Viking raids eventually transformed this peaceful merchant culture, the foundations laid by Anglo-Frisian trade remained vital to medieval economic development.

References and Further Reading

Primary Sources

- Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People

- Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

- Carolingian Annals and Capitularies

- Archaeological Reports from Hamwic, Ipswich, and Dorestad

Modern Studies

- Michael Pye, "The Edge of the World: A Cultural History of the North Sea and the Transformation of Europe" (2014)

- Richard Hodges, "Dark Age Economics" (2012)

- Christopher Scull, "Early Medieval (Late 5th–Early 8th Centuries AD) Cemeteries at Boss Hall and Buttermarket, Ipswich" (2009)

- John Hines, "The Scandinavian Character of Anglian England" (1984)

- Sonia Chadwick Hawkes, "The Early Saxon Period" in "The Archaeology of Anglo-Saxon England" (1976)