Frisian Longhouses (6th–9th Century)

Early medieval Frisian longhouses were distinctive, practical dwellings built to withstand the storm-swept coasts and waterlogged terrain of the North Sea marshlands. They functioned as combined homes and barns (byre-dwellings), sheltering both humans and livestock under a single roof. Unlike Anglo-Saxon or Jutish homes, Frisian longhouses placed a strong emphasis on integrating the domestic and agricultural spheres within one elongated structure.1

Dimensions and Layout

Frisian longhouses typically measured 12 to 18 meters in length, though some examples extended up to 20 meters as herds and households grew. Widths were usually around 5 to 6 meters. The layout was distinctly linear, divided into three main sections:2,3

- Binnenhuis "inner house": The living area, containing the hearth, sleeping platforms, and domestic space.

- Middenhuis "middle house": A transitional space used for work, cooking, dairying, and in some cases containing a freshwater well.

- Buitenhuis "outer house": The barn or byre section, where cattle were kept during colder months.

The roof was typically 5–6 meters high at its ridge, with a steep pitch to shed rain and withstand coastal winds. The floor often sloped subtly from the living end to the barn end, aiding in waste drainage.

Construction Materials and Techniques

Due to the scarcity of timber on the salt marshes, Frisian builders adapted by constructing walls from stacked blocks of turf sod, often up to 1 meter thick. These sod walls provided excellent insulation and structural support. A timber frame (usually oak) was built using a three-aisled system, with two rows of interior posts supporting the roof via cross-beams. The roofing material was typically thatch made from reed or straw.

Reconstructed Anglo-Saxon dwelling showing the characteristic wattle and daub construction with a timber frame and thick thatch roof. While smaller than a Frisian longhouse, this structure demonstrates similar building techniques that would have been used throughout the North Sea region.

The roof framing technique known as the roof-beam bent (dekbalkgebint) featured beams placed on top of the posts, creating a stable arched structure that projected slightly beyond the wall line. This not only provided weather protection but also helped distribute the weight of the heavy thatch.

The floor was generally packed earth, possibly lined with straw or rushes, and sometimes clay or wood planks in high-use areas. A central manure gutter (grup) ran through the barn section to channel waste away, which was often dried and reused as fuel.

Livestock Integration

Frisian longhouses were notable for their integration of animals into the main dwelling. Cattle were tied along the side walls of the barn section, facing outward, with their hindquarters toward a central aisle. This aisle included a shallow trench for waste, allowing for hygienic management and daily mucking.

This integration provided warmth and security, particularly during winter, and allowed farmers to monitor their livestock closely. Separate storage buildings were used for hay and grain to prevent vermin and reduce fire risk.

Environmental Adaptation

To cope with the frequent flooding of the low-lying salt marshes, Frisian farmsteads were constructed on artificial mounds called terpen. Over time, repeated building and rebuilding created layered platforms of habitation. Excavations show evidence of sod walls, embedded timber posts, and turf reinforcement around the bases.

Frisian longhouses were deliberately low-profile and sturdy, designed to survive high winds and salty air. Their thick turf walls, thatch insulation, and multifunctional design were perfectly suited to the treeless, fertile, and flood-prone coastal environment.

Cultural Significance and Archaeological Evidence

Although not yet supported by direct archaeological evidence, this article proposes the possibility that Frisian-style longhouses may have appeared in early migration-period settlements in East Anglia, particularly in regions like Norfolk, where the coastal environment closely resembles that of Friesland. While speculative, this idea is grounded in several observable parallels:

- Environmental Parallels: The marshy, flood-prone landscapes of Norfolk mirror the Frisian salt marshes, making similar building adaptations likely.

- Linguistic and Toponymic Clues: Place-name and dialect studies reveal early Frisian influence in parts of East Anglia, suggesting migration and cultural transfer.

- Architectural Continuity: Broader traditions of longhouse-style buildings with integrated human and animal use can be found in other parts of Britain, such as Dartmoor, raising the possibility of regional variants rooted in shared North Sea traditions.

While no excavated structure in Norfolk has been definitively identified as a Frisian longhouse, the convergence of environmental, cultural, and linguistic evidence makes it plausible that such forms once existed in early Anglo-Frisian settlements. Future excavation and analysis may shed more light on this intriguing connection.

The Frisian longhouse was a reflection of an egalitarian agrarian society, where self-sufficiency and adaptation to nature were essential. Linguistic evidence (terms like binnenhuis and buitenhuis) and finds from terp sites like Ezinge, Hallum, and Firdgum confirm the consistent layout and building approach.

Reconstruction projects, particularly the turf longhouse at Firdgum, have provided critical insights into the building methods, lifestyle, and climate resilience of early Frisians. The presence of red ochre pigment on some turf walls hints at a possible decorative or symbolic tradition.

In all, the Frisian longhouse embodied a practical, deeply rooted relationship between farmer, animal, and land — a model of sustainable and resilient living in the early medieval North Sea world.

Anglo-Saxon Longhouses (Angles, Saxons, and Jutes)

Early medieval Anglo-Saxon longhouses, constructed by the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes in what is now England, typically differed from their Frisian counterparts in both layout and function.4 These dwellings were primarily residential-only buildings, often built in clustered villages with surrounding enclosures for animals and workspaces.

Dimensions and Layout

Most Anglo-Saxon longhouses were relatively modest in size. Ordinary houses measured about 10 to 12 meters in length and 4 to 6 meters wide, often forming simple rectangular plans.5 Larger structures, such as noble halls, could reach 15 to 25 meters, though these were exceptional.

Most houses were single-room structures, although some included internal partitions or a small separate chamber. The interior space was used for living, sleeping, and cooking, centered around a central hearth. Roofs were steeply pitched and thatched.6

Materials and Construction

Anglo-Saxon buildings used timber frames with wattle-and-daub walls or vertical planking. Posts were often sunk into the ground, though later buildings used foundation trenches or sill beams for improved stability.7

Reconstructed Anglo-Saxon longhall showing the characteristic timber frame with yellow-painted wattle and daub walls. Note the steep roof pitch and entrance design. This reconstruction demonstrates how these structures would have appeared during the early medieval period.

Roofing was thatch (straw or reed), and floors were packed earth, occasionally covered with planks or lime mortar.8

Livestock and Outbuildings

In contrast to Frisian longhouses, livestock were not kept inside Anglo-Saxon homes. Animals were housed in separate sheds, barns, or fenced yards nearby. This separation created cleaner indoor environments but required more complex farm layouts.9

Social and Cultural Role

While most Anglo-Saxon homes were humble and functional, elite halls (e.g., Yeavering, Lyminge) served as political and ceremonial centers, often richly decorated and significantly larger than standard dwellings. These halls were central to the mead-hall culture celebrated in works like Beowulf.10

Archaeological Sites

Important excavation sites include West Stow (Suffolk), Yeavering (Northumbria), and Lyminge (Kent), which provide substantial evidence of domestic architecture, village layouts, and variations in building size and style across regions.11

Jutish Longhouses (Kent and Southeastern England)

The Jutes, one of the Germanic tribes that migrated to Britain during the 5th and 6th centuries, settled primarily in Kent, the Isle of Wight, and parts of Hampshire. Their architecture closely resembled that of their Anglo-Saxon neighbours, with no distinctive longhouse form identified solely as "Jutish" in the archaeological record.12

Dimensions and Layout

Typical Jutish domestic buildings were modest rectangular timber structures, approximately 8 to 12 meters long and 4 to 5 meters wide. Most were single-roomed, although evidence from higher-status sites such as Lyminge suggests partitioned interiors and multi-phase buildings indicating evolving use over time.13

Jutish halls, especially those associated with early royalty or elite activity (as in Lyminge), could reach 20 meters or more in length, similar to contemporary Saxon or Anglian great halls.14

Construction and Materials

Jutish buildings were timber-framed, using post-in-trench or posthole construction. Wall infill was commonly wattle-and-daub, and roofs were thatched with local reed or straw. Posts were primarily oak and set directly into the ground.15

Floors were typically of beaten earth, though high-status buildings may have included areas with clay or timber floors. The construction style was practical and closely aligned with the early Anglo-Saxon tradition.

Livestock and Subsistence

As with the Angles and Saxons, Jutish homes did not include livestock within the dwelling. Animal husbandry was central to rural life, but animals were housed in separate barns or pens within the homestead. There is no evidence of byre-style integrated longhouses in the Jutish archaeological footprint.

Pre-Migration Context

Before their migration to Britain, the Jutes are believed to have originated from the Jutland Peninsula in present-day Denmark. While archaeological material clearly attributed to Jutish identity in this region is sparse, it is assumed they shared architectural traditions with their North Sea Germanic neighbours, particularly the Anglo-Frisian and Danish longhouse cultures. In these regions, long timber-framed halls with simple partitioning and integrated agricultural use were common.

Early Iron Age and Migration Period dwellings in Jutland often consisted of longhouses with central hearths and timber framing, and some included space for livestock. These structures typically measured 12–20 meters long, with thatched roofs and walls of wattle-and-daub or plank construction. Though such designs were not uniquely Jutish, they form the architectural and cultural background from which later Jutish houses in Kent likely evolved.

Cultural Notes and Sites

The site of Lyminge in Kent offers the most insight into Jutish elite architecture. Excavations have revealed a large feasting hall dated to the 6th or 7th century, along with evidence of continuous domestic occupation, religious conversion, and royal patronage. This suggests that while ordinary Jutish houses were similar to Anglo-Saxon homes, elite structures could reach impressive scale and symbolic importance.

The Jutish architectural legacy blends almost seamlessly with the broader Anglo-Saxon tradition. Nevertheless, sites like Lyminge reflect a regionally significant hub where Continental and Insular traditions merged in the early medieval period.

Danish Longhouses (Pre-Viking Period, 6th–8th Century)

Danish longhouses of the pre-Viking period were substantial, multifunctional structures that laid the foundation for the larger and more elaborate Viking halls of the 9th–11th centuries. These early longhouses reflect a settled, agricultural society with increasing complexity in architecture.

Structure and Dimensions

Pre-Viking Danish longhouses were typically 15 to 30 meters long and 5 to 6 meters wide, with some reaching up to 35 meters. Many featured curved or bowed walls, a distinctive characteristic of Scandinavian architecture that gave the buildings a "boat-like" footprint.

The layout was generally tripartite:

- A residential end for family activities and sleeping,

- A central workspace or entry hall (sometimes with opposed side doors),

- A byre section for livestock.

This arrangement demonstrates the byre-house model, shared with Frisians, where people and animals cohabited in different zones under one roof.

Materials and Framing

Danish longhouses were constructed using a robust timber post-frame system. Two rows of internal posts supported the ridge-pole and rafters, forming a central aisle with flanking side aisles. Oak and pine were common building materials.

Walls were made of horizontal planks, wattle-and-daub, or vertical boards, depending on region and availability. Roofs were steeply pitched and covered with thatch, sometimes layered with turf or birch bark for extra insulation.

The structural stability of these houses was enhanced by external buttresses and deeply embedded corner posts. Later developments began to eliminate interior posts in favor of wall-supported trusses, a precursor to Viking-era hall designs.

Livestock and Internal Layout

Livestock, primarily cattle and sheep, were housed in the byre section of the longhouse during colder seasons. Stalls lined the sides of the rear section, and a central manure trench helped with drainage and cleanliness, much like Frisian practice.

The living area contained a long hearth running down the center or offset to one side. Benches and bedding were placed along the walls, and internal partitions may have created storage nooks or semi-private areas.

Environmental and Cultural Context

These buildings were well adapted to the Danish climate, with thick thatch, limited openings, and integrated animal heat. The architecture also reflects a growing social stratification, as wealthier farms began to develop larger homes and more complex outbuildings.

Although not as monumental as later Viking halls, pre-Viking Danish longhouses show a clear architectural lineage leading to the high-status feasting halls and fortresses of the 9th century.

Key archaeological sites include Vorbasse and Jelling, which have revealed longhouses with standard layouts, internal divisions, and associated farm complexes — all indicative of a stable, agricultural society with growing hierarchical organization.

A Note on Longhouses and Viking Associations

It is worth noting that the longhouse is too often exclusively associated with the Viking Age in popular imagination. While Viking longhouses are certainly striking examples of the form, the longhouse as a building tradition long predates the Vikings themselves. Its roots stretch back through the early Iron Age and the Migration Period, evident across the North Sea world from Frisia to Jutland well before the first Viking raids.

Reconstructed Viking Age longhouse built on an elevated site with sod walls and turf roof, showing similarities to Frisian dwelling forms. Note how horses graze nearby, similar to how livestock would have been kept in proximity to Frisian settlements.

The Frisians, Jutes, Angles, and Saxons all employed longhouse structures adapted to their environments and cultural needs. These early longhouses — functional, agricultural, and domestic — laid the groundwork for later Norse designs. The Viking longhouse should therefore be seen as a continuation and elaboration of a deeply rooted architectural tradition rather than a uniquely Norse innovation.

Understanding this broader context not only enriches our view of the Viking Age but also restores due credit to the lesser-known, yet foundational, societies that shaped early medieval Northern Europe.

Epic Echoes: Longhouses in Beowulf

One of the most iconic representations of a Germanic longhouse in literature is Heorot, the great hall of King Hrothgar in the Old English epic Beowulf. Though a work of poetry rather than architecture, Beowulf offers a vivid cultural window into the symbolic power of these buildings in early medieval Northern Europe.

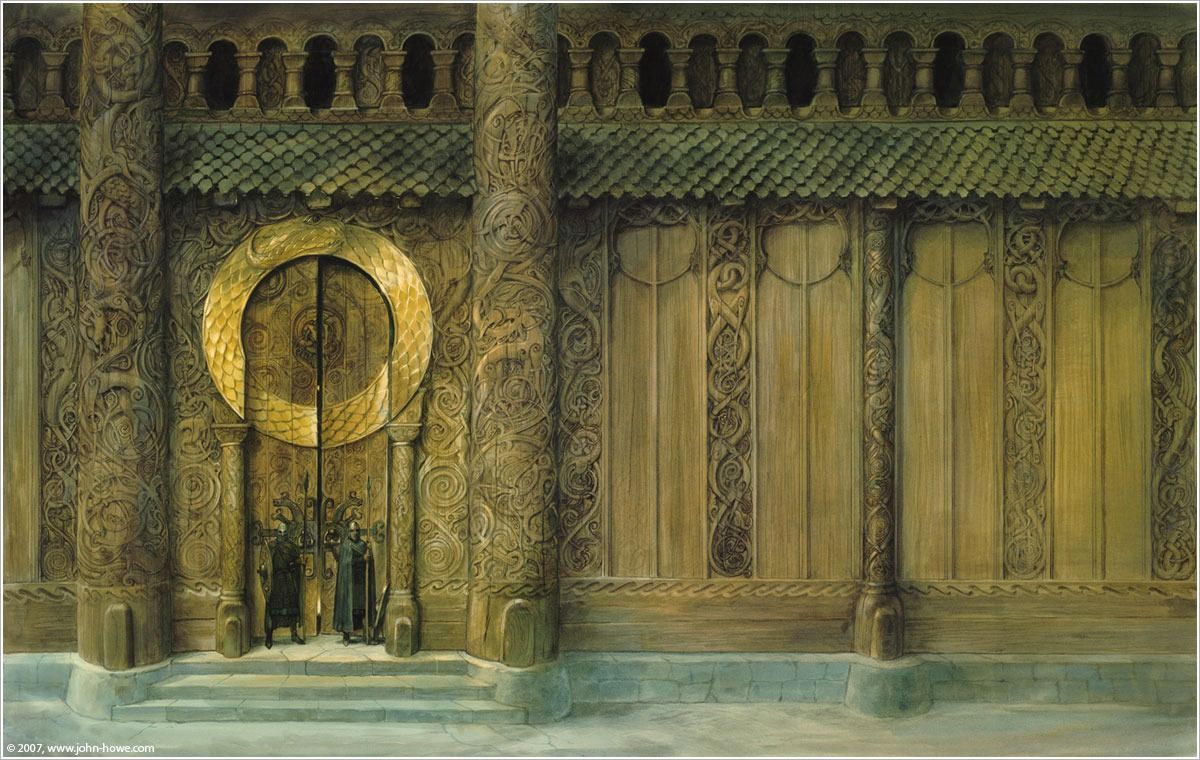

Artistic reconstruction of an elaborately decorated Anglo-Saxon great hall entrance, inspired by descriptions in Beowulf. While most dwellings were modest, elite halls could feature ornate decoration with intricate woodcarving. This artistic interpretation by John Howe shows the mythological and cultural significance of such structures. © 2007 John Howe.

Heorot is described as a grand wooden hall, richly adorned, and built to serve as the center of royal authority and communal identity. It is the place where warriors feast, receive gifts, make oaths, and hear tales — all critical functions of a hall in early Germanic society. Its role transcends the material: it is a beacon of civilization, kinship, and power, and its desecration by the monster Grendel is an assault on the very fabric of social order.

While no archaeological site perfectly matches the grandeur of Heorot, the great halls uncovered at Yeavering, Lyminge, and Lejre (Denmark) reflect the architectural reality behind the poem's imagery — large timber buildings with ceremonial significance. These halls, like their literary counterpart, were more than homes: they were cultural heartlands, binding communities together through shared memory, leadership, and ritual.

By placing the longhouse at the center of its narrative, Beowulf preserves a vision of the hall not only as a dwelling, but as a symbol of identity, legitimacy, and legacy — a theme resonant with archaeological discoveries across the Anglo-Frisian and Danish world.